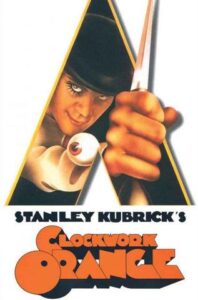

It is hard to add a lot of new insight to a movie that has been reviewed thousands upon thousands of times and is liked so much that it is ranked #46 in the AFI’s Top 100 List of Greatest Movies. With that said, most reviews of A Clockwork Orange were written in 1971, when the movie was released. I watched this movie for the first time in 2011, 12 years after the death of its director, Stanley Kubrick (The Shining, Full Metal Jacket). To date, this will be the oldest movie that I have reviewed.

It is hard to add a lot of new insight to a movie that has been reviewed thousands upon thousands of times and is liked so much that it is ranked #46 in the AFI’s Top 100 List of Greatest Movies. With that said, most reviews of A Clockwork Orange were written in 1971, when the movie was released. I watched this movie for the first time in 2011, 12 years after the death of its director, Stanley Kubrick (The Shining, Full Metal Jacket). To date, this will be the oldest movie that I have reviewed.

A Clockwork Orange is a strange movie. Stanley Kubrick was a peculiar director. He’s a man who was never afraid to push the envelope regardless of what his critics and the public might think. This was just the fourth movie he directed during my lifetime and the first since his controversial Tom Cruise/Nicole Kidman movie Eyes Wide Shut (1999) that flirted with an NC-17 rating. This was the only movie of his that he was able to see in the movie theater. While most people left the film wondering what they had just watched, I thought this movie was a stroke of genius. The Shining (1980), Full Metal Jacket (1987), and Spartacus (1967). These are landmark movies. I recommend any film fan see all five films mentioned above. The legendary Kubrick was nominated for a Best Director Academy Award four times between 1966 and 1975 but came up empty-handed each time.

A Clockwork Orange certainly isn’t for everyone. There is a considerable part of the population that will either be offended by the movie or won’t have the stomach to watch it. If you go in with an open mind, expecting anything and everything, you will leave feeling as if you have just witnessed something both profound and enjoyable. This is one of those movies that leaves you wanting to immediately read the novel it was based upon after its conclusion. Set in near-future (the actual year not stated) England, the movie examines the nature of violence as twenty-something Alex (Malcolm McDowell – Voyage of the Damned, Time After Time) and his three Droogs. The men spend the first act of the movie getting high and their adrenalin pumping at the Korova Milkbar before committing acts of debauchery on undeserving people. These include beating a homeless man to a pulp, terrorizing and paralyzing a successful writer, and gang-raping his wife right in front of him. Alex is the leader of his little gang and makes it known to them on more than one occasion, even slicing the hand of Dim (the dummy of his group) when Alex believes he got out of line with him. Alex is cold-hearted, thinks only of himself, and shows no sympathy for anything he has done or anyone he has hurt.

But when his three Droogs attack him and leave him to get arrested after one of Alex’s assaults that resulted in the death of a woman (who he repeatedly smashed in the skull with a piece of artwork), he is prosecuted for murder and sentenced to 14 years in federal prison. It is here that Act II of the three-act movie begins. Here, we see a vulnerable Alex for the first time, looking like a regular guy, with his hair down, without the bizarre makeup and the same set of garb that he had been sporting before this point for the first time. He is humble, scared, and facing 14 years of misery ahead of him. Order and the prison way of life are not something that is for him, and he fears for his next 14.

When he receives an offer for a psychotherapy medical experiment that could cut his sentence tremendously, Alex jumps at the opportunity. Through the test, Alex is forced to watch a series of disturbing movies relating to murder, rape, and other types of violence. And when I say forced to watch, I mean his eyelids are kept open so he couldn’t even blink. Through this Ludovico behavior modification technique, Alex becomes mentally and physically sick when he becomes confronted with these types of wrongdoing. The purpose of the test is to expedite the rehabilitation process to clear the jail of criminals to free up room for political prisoners. What Kubrick did well was he did not rush Act II. We see and believe the changes in Alex. As easy as it was to dislike him in Act I (and it is very, VERY easy to hate him as he clearly shows no remorse in anything he does), it becomes easy to empathize with him in Act II. In addition to abhorring violence, he now feels tortured when listening to Beethoven, his previously most beloved musician.

In an interesting turn of events, Kubrick was forced to withdraw A Clockwork Orange from England after several juvenile gangs admitted copycatting the crimes depicted in the movie. In America, this movie initially received an X rating. A scene had to be trimmed by half a minute to get it back down to an R rating. While controversial, many people understood and even appreciated the message that Kubrick was trying to make. The movie attacked the increasingly aggressive movement of youth violence while also successfully examining social injustices and exploratory medical procedures in which the doctors care not about the patient but about producing results that the public wants to hear. Kubrick also took aim (albeit a bit forced) at the government and the things government officials try to do to gain public fanfare, cover up lies, and avoid being at the center of controversy.

Plot 8/10

Character Development 9/10

Character Chemistry 7/10

Acting 7.5/10

Screenplay 10/10

Directing 9/10

Cinematography 9/10

Sound 10/10

Hook and Reel 8/10

Universal Relevance 8/10

86.5%